You’re Still Here. Not Everyone Had That Choice

If you're reading this, you're still in the game. And that's not nothing, it's everything.

Warning: This is a hopeful story.

But you’ve got to do some work to get there.

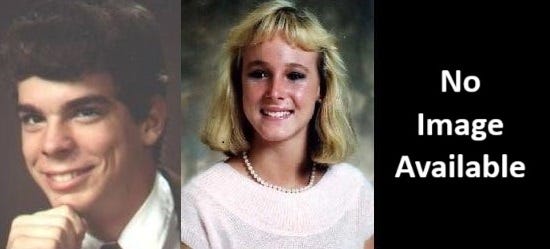

Andrea Bell was the most beautiful girl I’d ever seen.

The stereotypical California blonde, whose essence even a Beach Boys song couldn’t capture. She appeared permanently backlit, a corona of sunlight beaming through her feathered hair.

We first met in 1978, three weeks into 6th grade, the transition year. You know, when you start taking showers after gym class.

I spent all summer working on my shower game, trying to get it down to six and a half minutes—the amount of time I was led to believe I’d have to get the job done.

But that’s a different story.

Her beauty was striking, intimidating the boys—and most of the girls—at our school, unfairly making her seem stuck up and unapproachable.

But I wouldn’t have approached her no matter what she looked like.

Painfully skinny and pre-pubescently insecure, I had no game with girls, even the ones who didn’t put Farrah Fawcett to shame (Google her).

For some reason, that even the Gods of Olympus still fail to comprehend, she walked over and started talking to me.

Me?

Yes, me.

But why?

She was beautiful, I was not.

The math didn’t add up.

Yet, even the skinny, socially awkward dork that I was, knew better than to look a goddess-like gift horse in the mouth, and we became fast friends.

Andrea was always nice to me. Always kind.

I’m sure both her girlfriends and boyfriends asked endlessly, “why are you talking to that skinny dork?”

Fortunately for me, she had more than enough social cred to blow them off without risking her status.

And I fully believe my friendship with Andrea kept me from getting beaten up or falling off the social ladder in middle school, and eased my entry into high school.

Tom Damski was the strongest kid I’d ever seen.

Kid? Who am I kidding?

That’s a misnomer if I ever spoke one.

Six foot two, two hundred and ten pounds of pure muscle, he looked like the statue of David—if David was on roids.

I first met Tom in freshman year, when we both tried out for the football team.

I had no business being there. He did.

During a game in sophomore year, when half the team must have been out with the plague, or we were up by 100-points—the only reasons I can imagine in which I would have been in the game—a play was called that featured Tom.

As fullback, he was supposed to look for an opening in the offensive line, specifically, one made by the left guard, and run through it.

And if there was no opening, he was supposed to make his own.

I knew this play by heart, as I was said left guard.

When the ball snapped, I threw all 145lbs-soaking-wet-holding-a-brick of myself at the 200lb tackle across from me, not moving him in any way, shape, or form.

That didn’t faze Tom, who ran where the hole should have been, and created one, by running right over my back—necessitating six weeks on crutches, courtesy of the torn cartilage in my knees.

They still make a crunching sound to this day.

That’s the visual I get when I think of Tom; a boy god, breaking through the line of scrimmage, a serpentine of defenders dragged behind him like the tail of a New Year’s dragon.

But Tom’s strength wasn’t contained to the gridiron.

In a time and place where punk rock ruled supreme, he took great pleasure in being a decidedly unpunk rocker—with the long hair to prove it.

While new bands like Black Flag, The Dickies, and X were in the Walkman's of his contemporaries, Tom lived in a self-imposed musical time warp where only Foghat, Boston, and Kansas existed.

And though not a bully, he lived for the opportunity to be “challenged” by those who didn’t share his musical tastes.

Like the time he and a friend went to the Whisky a Go Go on the Sunset Strip and stood stone still in the middle of the slam pit until a punker tried to make him move.

That was a bad choice.

In a matter of minutes, ten or more punks had busted noses and black eyes. Tom barely broke a sweat.

I recently looked for Tom’s picture in our senior yearbook, but keeping totally in character, it only had his name, and the caption, “No image available.”

Darrell Esgar was the nicest person I’d ever met.

Made more remarkable by the fact that he didn’t really fit in in high school.

The cool kids didn’t like him because of his off-brand clothes, unkempt hair, and awkward way of talking. And the accompanying scorn he received would have been the perfect excuse to withdraw into himself and shun others.

But that wasn’t Darrell.

There wasn’t a stack of books he wouldn’t carry for you, a test he wouldn’t help you with, or a favor he wouldn’t grant.

Once, while driving to school, he saw a classmate—a popular girl, who, on more than one occasion, had been cruel to him—stranded by the side of the road.

Without even thinking, Darrell—who was handy with engines—pulled over to help.

After assessing the situation, he drove back to his house to get the proper tools and went to work on her car.

When it looked like she would be late, he drove her to school in his car, then went back to hers, and continued working on it until he got it running.

His reward was a tardy slip, and snide remarks spread through school by the damsel he rescued, that she got “that weird guy Darrell to help me.”

I can’t be sure, but odds say that I was probably a dick to Darrell at some point, because he occupied a social strata even lower than I did, and in the pre-bully prevention 80s, it was dog eat dog in high school.

And if I was, I regret it.

I’m 98.9% off Facebook.

I’d delete it in a Zuckerberg minute if it weren’t for three things;

The “Memories” surfaced each day from a time before my kids knew how to talk back.

My ever optimistic hope that Cory will finally resurface.

The “In Memoriam” page.

This last one is where alumni from my high school memorialize fallen classmates.

Andrea, Tom, and Darrell are all on that page.

One day, Andrea the beautiful, found a white spot on her tongue.

It was cancer.

The fight ebbed and flowed for years, but it took away parts of her tongue, jaw, face, and eventually, her life.

Tom the strong, stepped off a curb the summer after graduation and, while looking the wrong way, finally met his match in the form of a 67’ Buick LeSabre.

He died before the ambulance arrived.

Darrell the kind, was closing up shop with two co-workers when an ex-employee on a cocaine binge—whom he was friends with—entered through the back door.

He told them he was going to rob the store. They thought he was joking until he made Darrell bind his co-workers hands behind their backs with duct tape, before he did the same to Darrell.

After emptying the safe, he left the store. Then, worried that his friends would turn him in, re-entered, and shot them one by one, execution-style,

According to court testimony, Darrell was the last to die.

After watching his friends murdered in front of him, sweet, sweet Darrell told his killer, “You don’t have to do this. You can still get help.”

“I will help you.”

“I raised the gun to his head,” said the killer. “Darrell slumped forward and began to cry. Then I began to cry. And then I shot him.”

Beauty like Andrea’s should never die.

Nor should strength like Tom’s.

And certainly not kindness of the type that Darrell possessed.

But it does. And that’s the way it is.

I said this was a hopeful story—and it is.

It’s a tough slag.

You tack right, then left, and it’s hard to find that pure vein of hope.

But it’s there if you try. If you frame it right.

Sometimes life gets tough. Sometimes it’s a struggle.

I feel that way at times. We all do.

But when I do, I think about these three.

And I’m so grateful that I knew them, and that I’m here.

That I’m still in the game.

Because that’s everything.

Undoubtedly, you have your own Andreas, Toms, and Darrells.

Draw strength and inspiration from them and from those who’ve gone before you.

And live the best life you can.

That’s what I’m trying to do.

The world is a better place with you in it, Brian! Great writing.

Great peice, Brian. It really resonated with me.

Last Saturday night I attended my high school reunion (class of '79) at the Elks Club in Blawenburg, NJ.

We were a class of about 160 kids. The organizer of the reunion had a number of photos, mementos, etc. of our class. In two frames, were the senior pictures of some of our classmates. Looking closely, I realized the photos were of those we graduated with who have passed away (I counted 18 - a big number as far as I am concerned).

It became a topic of conversation from that point forward for the rest of the night for me. I mentioned to two friends in partial jest; my goal is not be included in that framed group when we get together again in five years. Glad to be here.