The Fine Line Between Scary Smart and Astonishing Stupidity

There's no creature more pathetic than the man who outwits himself.

Eric Eberwein was smart. Scary smart.

The moment he walked into Algebra II/Trig I knew he was a curve killer—the yardstick by which the rest of us would be measured.

And he looked the part.

Off-brand sneakers, tube socks up to his knees, cargo shorts, a faux football jersey—all topped by a mop of hair that never met a comb or dollop of styling gel.

The prototypical high school nerd.

It wasn’t long before Eric got a chance to demonstrate the power that lay in his overdeveloped cranium.

“Would anybody like to take a stab at this problem?” Mr. Hughes asked, pointing toward the chalkboard.

Eric’s hand shot up instantly.

“Ah, Mr. Eberwein? Please come on up.”

Eric strode to the front of the room with confidence. He took a dramatic pause, then turned to address the class.

With an authoritative tone and the cadence of a computer, he began to break down Mr. Hughes’ equation:

“Taking into account the concepts of the quadratic equation and the corresponding numerical coefficients, we can reduce these factors to their lowest common denominator.”

The class was mesmerized.

We were watching the next Newton. The next Einstein.

A man whose name would one day be spoken with the same reverence as that of Euclid, Archimedes, and Pythagoras.

There was beauty and grace in the way he dismantled the equation—arms waiving to punctuate points, hands slashing across the board, Xing out unneeded variables—like a conductor directing a symphony.

Then, as his performance reached its crescendo, he threw back his shoulders, tilted his head skyward, and, closing his eyes as if about to experience the rapture, exclaimed:

“The answer is 3x – 7.”

The room fell silent.

Mr. Hughes got up from his desk, walked over to Eric, and laying his hand on his shoulder said: “Wrong, Eric.”

It was just the first of many times this scenario played out over the course of the semester.

“The answer is 3 over π.”

“Wrong, Eric.”

“The answer is the hypotenuse of a triangle.”

“Wrong, Eric.”

“The square root of 747.”

“Wrong, Eric.”

“Seventeen.”

“No, wrong, Eric.”

Eric Eberwein was smart. Scary smart.

Except he wasn’t.

And as embarrassing as this all must have been for Eric, I had no sympathy for him.

In fact, I shunned him in the hallways, spurned all his advances of friendship, and talked shit about him behind his back.

That’s because I can’t relate to people like Eric.

You see, unlike Eric, I’m smart.

Very smart.

So smart, I’m stupid smart. Shockingly smart. Scary smart.

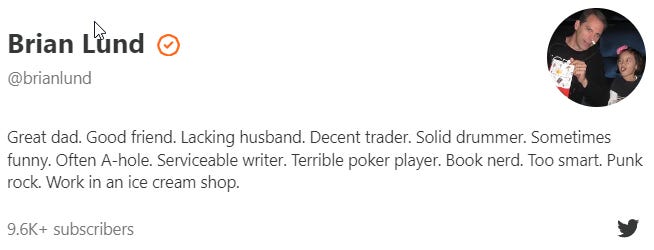

Have you seen my Substack bio?

It says it right there, “Too smart.”

(If we ever have a drink or two in a pub I’ll tell you about the “ice cream shop” part).

And I’m not just singularly smart, I’m smart across the board.

Math smart. History smart. Interpersonal relationship smart. Politically smart. Business smart. Marriage smart—but don’t ask my wife, just trust me on this.

In fact, I’m so smart I could be a billionaire. I just don’t want to be one.

Don’t believe me? Let me give you just one example of how smart I am.

It was the height of the dot-com boom and the domain flipping craze was in full swing.

Business.com had just sold for $7.5 million and speculators were rushing to register any words or phrases they thought might have value.

Mind you, these were not active internet businesses, just domain names.

A little late to the game, but not wanting to miss out on the action, and sure I had the insight to find a valuable domain that the proletariat public had overlooked, I began my search.

My ingenious idea was to start with obvious, well-known themes, then go downstream.

For example, Disney, Disneyland, and Disneyworld dot-com would surely be taken.

But what about character names? Maybe nobody had yet thought of Mickey, Pluto, or Donald Duck dot-com?

They had.

But I continued, going from idea to idea, brand to brand, concept to concept, trying to find a hidden gem out in cyberspace.

At one point I theorized that the names of classic TV shows might still be under the radar and racked my brain to come up with the most iconic—those whose value would only increase over time.

And then it hit me: Star Trek.

The original series came out before I was born, and despite being rerun constantly throughout my youth, I never watched the show.

But despite my ambivalence, I knew the series, movies, and characters were beloved by millions, of dorks—like Eric.

And if my hunch was right, there was a chance I could snag a related domain and make some big bucks.

StarTrek.com was taken of course. Enterprise.com too. So I went down the list of characters, starting with the lesser-known ones…

MisterChekov.com

MisterSulu.com

Scotty.com

DrMcCoy.com

Bones.com

LtUhura.com

But they were all taken.

It was no surprise that MrSpock.com was gone as well, so I almost skipped CaptainKirk.com, assuming it was also taken.

So, imagine my shock when I checked and it was unclaimed.

Instantly, I locked it up.

I knew it, I thought to myself.

I sat back in my chair, self-satisfied, intoxicated by my fantastic insight, my ability to see what others couldn’t, my sheer brilliance, all the while counting the guaranteed profits in my head.

A few days later, I called my best friend, a serious Trekkie, to inform him of my coup.

“CaptainKirk.com?” he asked. “You got CaptainKirk.com?”

“Yep,” I answered.

“Are you sure about that?” he continued.

“You sound surprised,” I said.

“It’s just hard for me to believe that a domain like that wouldn’t already be taken,” he said.

“Yeah, well, it obviously was missed. Not everyone can think like I do. I’m pretty fucking smart. Scary smart.”

“Uh huh? So, you’ve got CaptainKirk.com?”

“Yep.”

“Send me a link to the URL,” he said.

“No problem,” I said.

“Okay, I got it,” he said. “C-A-P-T-A-I-N-K-I-R-K dot com,” right?

“Yes!” I shouted, irritated at the repeated questioning.

And looking down at my domain receipt, repeated back to him….

“CAPTAIN, KIRK, DOT, COM.”

“C-A-P-T-I-A-N….”

“Oh? Wait?”

Realizing that someone you thought was scary smart isn’t can provoke a variety of reactions.

If it’s a casual acquaintance, maybe there’s an odd curiosity.

With a close friend or relative, you’re disappointed

If it’s a parent or grandparent, it’s unsettling—especially if you’re still a kid.

When it’s someone who manages your money, teaches your kids, or is about to perform your heart transplant, it’s terrifying.

And when it’s you, it’s humiliating.

I probably should have been nicer to Eric.

Way to go BRAIN

This story sounds familiar.